important stories of conservation

Left: Mellerud rabbit l Middle: Scanian geese l Right: Norwegian Fjord horse

5.1 Denmark

The Jutland horse

The Jutland horse is considered as Denmark’s national draft horse, and it has a studbook that dates back to 1881. The breed was used as a draft horse in farming, but like many other Nordic native horse breeds, the population declined significantly after the Second World War. Consequently, the number of breeding mares is currently at 100, with only a few foals being born annually. Increasing or maintaining the number of breeding animals is therefore difficult. The use of few stallions led to inbreeding problems in the population in the 1980s, and since then the Jutland horse breeding association has been working toward increasing the number of horses. During a project between 2017 and 2019, the use of optimum contribution selection (OCS) to control for inbreeding was tested in the Jutland horse population. It was found that the use of OCS can significantly slow down the rate of inbreeding per generation.

Read more at: H. M. Nielsen & M. Kargo (2020) An endangered horse breed can be conserved by using optimum contribution selection and preselection of stallions, Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section A — Animal Science, 69:1-2, 127-130,

DOI: 10.1080/09064702.2020.1728370

DOI: 10.1080/09064702.2020.1728370

Danish Shorthorn

Studies considering the genetic diversity and relationship of different old Danish breeds found that the Danish Shorthorn has an alarmingly high genomic inbreeding value (33%) (Szekeres et al., 2016). This means that the Danish Shorthorn has a small population that exhibits low genetic diversity, and continued breeding within the enclosed small population without control-measures or introduction of new genetic material will increase the accumulated inbreeding, and therefore increase the consequences of inbreeding (e.g., reduced disease resistance and reduced fertility). Subsequently, a project to map the genome of the Danish Shorthorn population was carried out between 2019 and 2020. The goal of the project was to determine both the genetic variation and relationship between the Danish Shorthorn and other shorthorn populations with the focus on possible gene renewal into the Danish Shorthorn population to improve the future sustainability of the breed. The authors found that selection and import of 2 Northern Dairy Shorthorn bulls from the UK and the use of OCS can be used in future breeding to improve the population size of the Danish Shorthorn in the future.

- End report Anna A. Schönherz, 2021, Dansk Korthornsavl i Fremtiden – Genomisk Kortlægning af Korthornpopulationer.

5.2 Finland

In 2024, Finland is celebrating its 40-year anniversary for the implementation of national conservation strategies and activities for the animal genetic resources. Over the years, conservation activities have evolved from a framework established by authorities and the efforts of a few enthusiasts into a coordinated and research-oriented conservation approach. For example, Finland adopted a unique and innovative approach for safeguarding by gathering rare breeds on governmental prison farms. The groundbreaking initiative not only contributed to the conservation of endangered livestock but also provided purposeful work for inmates, which created a mutually beneficial relationship between the conservation efforts and the prison system. In 1984, the first cows, bulls and calves of Eastern Finncattle and Northern Finncattle arrived at two different prisons, Sukeva and Pelso prison farms, respectively. The conservation and breeding flock of Finnsheep and endangered Kainuu Grey sheep was established on the Pelso Prison farm. Northern Finncattle, Finnsheep and Kainuu Grey sheep gene bank herds were maintained for almost 40 years until the Prison and Probation Service of Finland (Rikosseuraamuslaitos) ceased this activity for live animal gene banking in 2022. Currently, these conservation herds are located on the educational farms of three vocational colleges: AhlmanEdu Vocational college in Tampere (Western Finncattle), Kainuu Vocational college (Eastern Finncattle) and Vocational College Lappia (Northern Finncattle. Finnsheep and Kainuu Greysheep). Moreover, the conservation of the Finnish Landrace chicken was initiated in 1998. The Finnish National Program considers common farm animal species as well as the honeybee (i.e., Nordic Brown bee), domestic reindeer and the native dog breeds.

Throughout their history, both the Eastern and Northern Finncattle breeds have experienced several critical turning points that have shaped their journeys. The large-scale evacuation of more than 20,000 northern Finncattle to Northern Sweden during the Lapland war in 1944-1945 saved the breed temporarily. Post-war agricultural intensification pressured farmers to replace local breeds with more efficient dairy breeds, shrinking the population to less than 30 individuals by the 1980s. A few dedicated pioneers began efforts to save the breed, and the newly established official conservation program coordination took over conservation. This effort has been successful, resulting in a stable population of approximately 850 breeding females today. Lately, the breed has gained significant visibility and recognition through several multidisciplinary research projects.

A similar event occurred with Eastern Finncattle, involving evacuation from the lost Karelia during World War II and subsequent efforts by a few pioneers to initiate conservation in the 1970s and 1980s. The breed's exceptional suitability for grazing has boosted its popularity in recent decades, and its population is now approaching 2 000 individuals.

Research activities have played a crucial role in the implementation of genetic resources program since the beginning. Finland was a pioneer in population genetics research and in enhancing genome level information. An open-minded approach has enabled the use of cutting-edge technologies. For example, in 1992, an Eastern Finncattle bull calf was born using artificial reproductive technologies (in vitro embryo production) in laboratory successfully. In recent decades, genetic resources have been recovered to the gene bank by producing embryos from post-mortem materials, allowing emergency harvesting of reproductive material. Additionally, cooperation with legislative authorities has been effective, exemplified by adjustments of legislations given by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry to allow the collection of sperm from the epididymides for both gene banking and breeding purposes. In the near future, preservation of skin tissue samples for animal genetic resources conservation will be implemented.

For more information

- Juha Kantanen (juha.kantanen@luke.fi)

- Petra Tuunainen (petra.tuunainen@luke.fi).

5.3 Iceland

Origin

The Icelandic farm animals have a unique position among Nordic farm animals. For each species of animals there is only one breed except for sheep and leader sheep. Animal breeding is based on breeds that have been isolated for over 1100 years, since the settlement period AD 874 – 930 and can be considered as a living gene bank for old Nordic farm animal breeds. Some import of live animals for breeding purposes occurred in earlier times but it is known that their influence on local breeds were minimal.

Conservation

The import of live animals is tightly regulated due to the risk of diseases; therefore, the breeds have remained genetically closed. Conservation of farm animals in Iceland began in the early 1960s when there was a need to pay attention to the endangered goat breed. In 1965 The Icelandic Farmers Association was obligated to work on the conservation of goats and leader sheep by the Act on livestock breeding. The first genetic resource council for AnGR was established in 1984 and celebrates 40 years of conservation work in 2024. From 2009 the Genetic Resource Council has issued a National Strategy Plan for Animal Genetic Resources which is updated every five years. Iceland has participated actively in the Nordic co-operation first from 1984; Nordic Gene Bank for Farm Animals (NGH), and from 2007; Nordic Genetic Resource Center (NordGen).

Goat breed

The Icelandic goat breed has been endangered for a long time and has suffered at least two serious bottlenecks when the number of animals went under 100. Conservation of the breed began 60 years ago when pedigree and phenotypical information on the breed was collected, and subsidies were granted for winterfed goats. A conservation plan was issued in 2012 with great emphasis on increasing the number of animals, production development, registry, and use of AI bucks to reduce inbreeding. Today the breed has achieved success and is becoming increasingly popular among breeders. The number of animals has increased from 875 (2012) to 1875 (2022). Inbreeding is high and the effective population size (Ne) was estimated under 10 animals (Baldursdottir et.al., 2012). Recent (unpublished) research shows that conservation work has been successful, indicating that the effective population size is increasing and inbreeding level is decreasing.

Leader sheep

The Icelandic leader sheep have been known to exist in Iceland since the settlement. The leader sheep was considered a subpopulation within the sheep population until 2017 when it was defined as a separate breed. The leader sheep is an example of subpopulation of sheep breed that has been successfully conserved. In the middle of the 20th century the population experienced a major bottleneck due to a disease eradication programme.

Leader sheep are graceful and prominent in the flock with alertness in the eyes, normally going first out of the sheep house, looking around in all directions, watching if there are any dangers in sight and walking in front of the flock when driven to or from pasture. There are many stories about leader sheep and their ability to sense bad weather and how they lead the flock home before a storm.

Inbreeding has been successfully controlled during the last few decades and leader sheep rams are kept in AI stations. The number of pure-bred animals is under 1000 and the total number including crossbreds is around 3500. The breed is defined as endangered.

Landrace chicken

The so-called settlement chickens are descendants of a group of chickens collected in Iceland by Dr. Stefán Adalsteinsson during 1974-1975. The group was collected in an attempt to try to save the remains of the chicken breed believed to have been brought to Iceland with the settlers 1100 years ago. The estimated number of birds today is 2000-2500. The effective population size (Ne) has been estimated to 36 (Gudmundsdottir, 2011).

Icelandic sheepdog

The Icelandic sheepdog is believed to be among the animals that were brought to Iceland with early settlers during the settlement period. The population underwent a drastic bottleneck in the early 20th century and the current population descends from only a few individuals. The number of founders estimated from pedigree was 44 (Olafsdottir & Kristjansson, 2008). Today there are between one and two thousand dogs registered in Iceland and over 11 000 registered in other countries.

For more information

- Birna Kristín Baldursdóttir (birna@lbhi.is)

- Thorvaldur Kristjánsson (thorvaldur@rml.is)

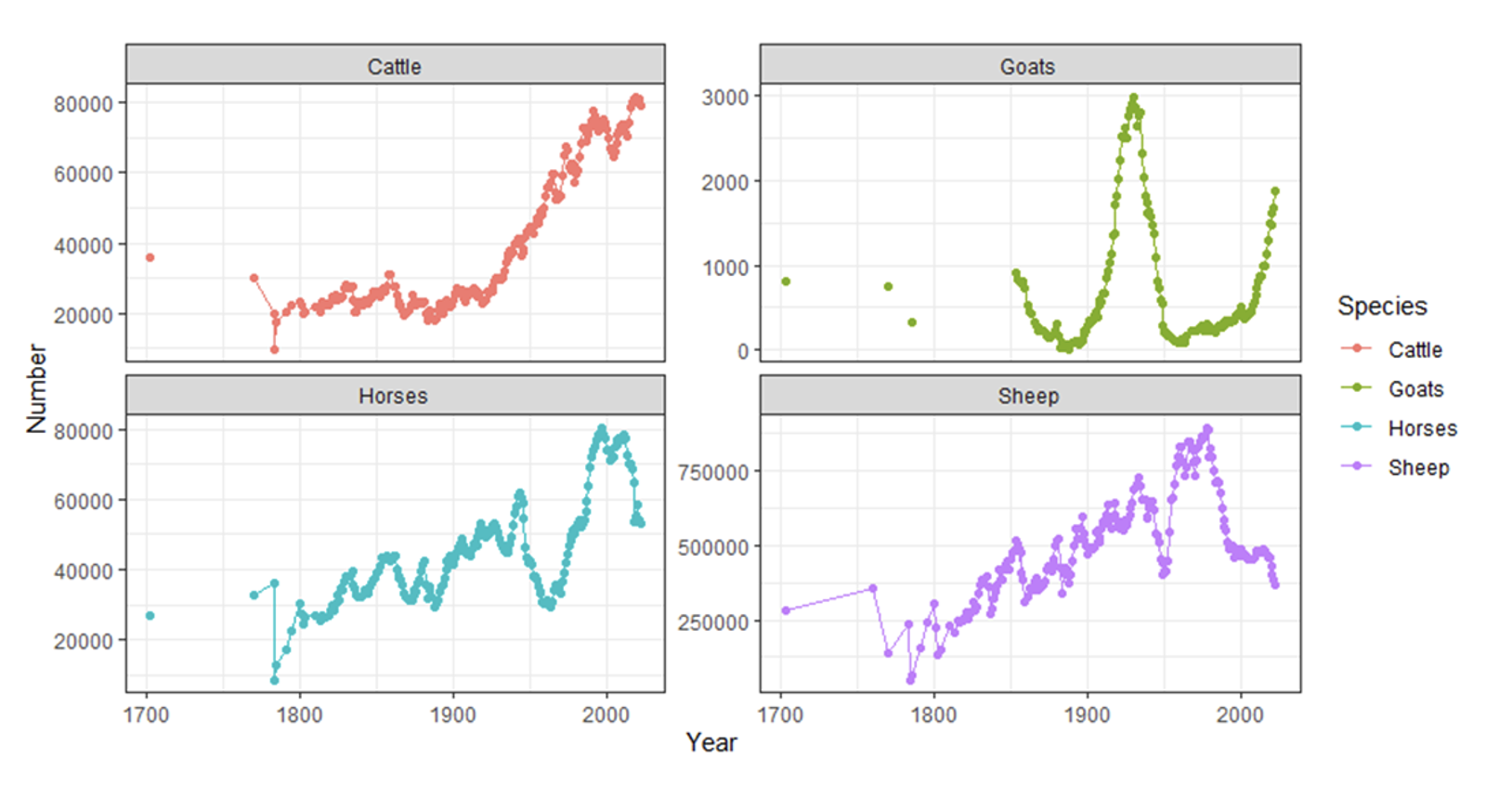

Figure 17: Number of animals 1703–2022.

Source: Hagskinna 1997 and Statistic Iceland, 2022.

Source: Hagskinna 1997 and Statistic Iceland, 2022.

5.4 The Faroe Islands

The Faroese horse

The Faroese horse is a small horse native to the Faroe Islands. A recent study shows that the breed is closely related to the Icelandic horse, Shetland pony and the North Atlantic breeds. The population of the Faroese horse has decreased significantly due to the use of larger horses for heavy agricultural equipment and the export of Faroese horses to the British coal mines in the 1900s. In the early 1900s, the breed suffered a severe bottleneck, and the breed almost went extinct as there were less than 10 horses left alive in the 1960s. Some enthusiasts found the remaining horses of the breed and started a rescue operation. However, due to the limited horses left, all living horses today are descendant of only five horses, and some of them were also related. The breed association for Faroese Horse was established in 1978, and the population size of the Faroese horse has slowly increased since. In 2021, the highest number of living horses, 94 individuals, were noted. However, in 2022, there was a population decline of 8.5% because 10 horses were lost and there were only two new foals born. A further decline was seen in 2023, when seven horses were lost due to age and illness, while three foals were born. By the end of 2023, there were 82 live horses in the population (Figure 17).

In March 2024, the first ever action plan considering the Faroese horse was released. The action plan outlines the different actions that are advised to be taken to further improve the status of the breed. The execution of the action plan has already begun, and the use of artificial reproductive technologies for gene banking is ongoing (e.g., systematic semen collection and embryo transfer). The slow increase in population number of the Faroese horse since the 1960s, the increased awareness and characterization of the breed and the successful use of control tools such as optimum contribution selection (OCS) marks a slow success story of conservation on the Faroe Islands.

In March 2024, the first ever action plan considering the Faroese horse was released. The action plan outlines the different actions that are advised to be taken to further improve the status of the breed. The execution of the action plan has already begun, and the use of artificial reproductive technologies for gene banking is ongoing (e.g., systematic semen collection and embryo transfer). The slow increase in population number of the Faroese horse since the 1960s, the increased awareness and characterization of the breed and the successful use of control tools such as optimum contribution selection (OCS) marks a slow success story of conservation on the Faroe Islands.

For more information:

Jens Ivan í Ger∂inum (jiig@bst.fo)

Jens Ivan í Ger∂inum (jiig@bst.fo)

Figure 18: The Faroese horse population.

5.5. Norway

The Norwegian Genetic Resource Centre, part of the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research (NIBIO), is a competence centre for the conservation and sustainable management of genetic resources for food and agriculture and provides technical assistance to all actors in the national conservation work. The centre monitors the status and development trends of the national genetic resources for food and agriculture in Norway and reports the status of these nationally and internationally. It also acts as an advisory body to the Norwegian Ministry of Food and Agriculture.

In 1990, a survey revealed that four of Norway's six endangered cattle breeds had fewer than 50 breeding cows, with none recorded in a proper pedigree database. The situation was critical, requiring urgent action. Thanks to the systematic conservation measures for over more than three decades, none of the native endangered breeds of cattle, horse, sheep and goat were any longer classified as critical endangered in year 2023 (i.e., all the breeds have more than 300 recorded breeding females in their population). The success of the conservation work on these breeds is roughly explained by the following key factors:

In 1990, a survey revealed that four of Norway's six endangered cattle breeds had fewer than 50 breeding cows, with none recorded in a proper pedigree database. The situation was critical, requiring urgent action. Thanks to the systematic conservation measures for over more than three decades, none of the native endangered breeds of cattle, horse, sheep and goat were any longer classified as critical endangered in year 2023 (i.e., all the breeds have more than 300 recorded breeding females in their population). The success of the conservation work on these breeds is roughly explained by the following key factors:

Pedigree databases

- Tracking kinship is crucial in breeding, especially in small populations, to minimize inbreeding and to monitor population trends.

- Appropriate pedigree databases for the native endangered breeds have thus been developed or strengthened for the livestock species of cattle, sheep, goat and horse.

- Registration is voluntary and free of charge but necessary for receiving subsidies.

- The pedigree databases function as herd books for the endangered breeds.

- Population trends are reported annually at both national and international levels.

Breeding associations and breed societies

Breeding associations and breed societies are essential networks for the farmers having three main tasks: facilitating the exchange of breeding material, promoting sustainable breeding practices and sharing traditional knowledge about suitable production systems.

Breeding associations and breed societies are essential networks for the farmers having three main tasks: facilitating the exchange of breeding material, promoting sustainable breeding practices and sharing traditional knowledge about suitable production systems.

Systematic expanding of the semen collection

Access to frozen semen is essential for breeding and gene banking. Since the late 1970s, and especially since the early 2000s, semen has been collected regularly from all the native breeds of cattle, sheep and goat. The semen is available for purchase by breeders. In addition, some doses of all donors have been put in a gene bank for long time storage.

Access to frozen semen is essential for breeding and gene banking. Since the late 1970s, and especially since the early 2000s, semen has been collected regularly from all the native breeds of cattle, sheep and goat. The semen is available for purchase by breeders. In addition, some doses of all donors have been put in a gene bank for long time storage.

Sustainable breeding in small populations

Communicating the special challenges in sustainable breeding in small populations has been a key task in the Norwegian work on conservation of native endangered livestock breeds.

Communicating the special challenges in sustainable breeding in small populations has been a key task in the Norwegian work on conservation of native endangered livestock breeds.

Easy and free access to breeding advice

Since the early 1990s, farmers with endangered native breeds of livestock have had free access to advice on sustainable breeding in small populations from Norwegian Genetic Resource Centre. To assess the impact of breeding efforts between 1990 and 2020, effective population sizes (Ne) were estimated for the six endangered native cattle breeds every ten years in this period. The results show that the breeding work has been sustainable, with Ne increasing or remaining above 100.

Since the early 1990s, farmers with endangered native breeds of livestock have had free access to advice on sustainable breeding in small populations from Norwegian Genetic Resource Centre. To assess the impact of breeding efforts between 1990 and 2020, effective population sizes (Ne) were estimated for the six endangered native cattle breeds every ten years in this period. The results show that the breeding work has been sustainable, with Ne increasing or remaining above 100.

New uses

Finding new areas of use has been important for all the livestock species with native endangered breeds. The horses are no longer working animals; they are used in sports. The goat and sheep breeds are successful as landscape managers and in 2010 a local spinning mill started spinning knitting wool from the challenging wool from the endangered native sheep breeds. This has turned out to be a success and in 2023 the mill produced yarn from a total of six tonnes of wool, only from native sheep breeds. The native endangered cattle breeds are now mainly used for meat production. The increase of breeding females in the decade from 2014 to 2023 has been from 2852 breeding cows to 5509 (assembled figures for all the six breeds). This increase of 93% in population status is due to the increased number of suckler cows, see Figure 19.

Finding new areas of use has been important for all the livestock species with native endangered breeds. The horses are no longer working animals; they are used in sports. The goat and sheep breeds are successful as landscape managers and in 2010 a local spinning mill started spinning knitting wool from the challenging wool from the endangered native sheep breeds. This has turned out to be a success and in 2023 the mill produced yarn from a total of six tonnes of wool, only from native sheep breeds. The native endangered cattle breeds are now mainly used for meat production. The increase of breeding females in the decade from 2014 to 2023 has been from 2852 breeding cows to 5509 (assembled figures for all the six breeds). This increase of 93% in population status is due to the increased number of suckler cows, see Figure 19.

Production subsidies

A crucial factor in conservation success was the introduction of the production subsidies for the endangered native cattle breeds in 2000. This subsidy scheme was expanded in 2016 to also cover the endangered native breeds of sheep, goat and horses. While it is more a recognition of farmers' conservation efforts than a significant income source, this support is highly valued by the farmers.

A crucial factor in conservation success was the introduction of the production subsidies for the endangered native cattle breeds in 2000. This subsidy scheme was expanded in 2016 to also cover the endangered native breeds of sheep, goat and horses. While it is more a recognition of farmers' conservation efforts than a significant income source, this support is highly valued by the farmers.

Future challenges

While Norwegian farming sees fewer farms with livestock, this hasn't yet impacted the growing populations of the endangered livestock breeds. However, this positive trend could eventually be threatened without supportive agricultural policies.

While Norwegian farming sees fewer farms with livestock, this hasn't yet impacted the growing populations of the endangered livestock breeds. However, this positive trend could eventually be threatened without supportive agricultural policies.

For more information:

Nina Svartedal (nina.svartedal@nibio.no)

Nina Svartedal (nina.svartedal@nibio.no)

Figure 19: The number of breeding cows in 2014-2023, assembled figures for all the six native endangered cattle breeds in Norway, by cows in different production systems; suckler cows for meat production and dairy cows for dairy production.

Source: Norwegian Genetic Resource Centre.

Source: Norwegian Genetic Resource Centre.

5.6 Sweden

Sweden has been active in conservation since the 1970s, and even private companies began storing semen from bulls used for artificial insemination in the 1950s. Importantly, the international nature conservation conference, hosted in Stockholm in 1972, marked the beginning of efforts for preserving domestic AnGR. At this conference, it was decided that each country should be responsible for their animal genetic resources and to pay special attention to breeds with small population sizes. During a conference for the Nordic countries in the following year it was decided that each of the Nordic countries have the responsibility to conserve their own AnGR, and Nordic collaboration through a working group in the Nordic Council of Ministers was suggested. For Sweden, the investigation of Sweden’s national AnGR initiated by the Swedish government, marked the beginning of long-term conservation efforts. These efforts led to the important report: “Bevarandet av genresurser hos husdjur”.

Although they have the widest array of native breeds to manage, they have arranged studies that comprise estimating important genetic parameters for over half of the breeds. Positively, only 7% of the breeds fall under the category of unknown, which is a large accomplishment considering the number of native breeds residing in Sweden. Furthermore, the use of master students to analyse data has significantly increased the information regarding genetic parameters of the Swedish native breeds. Almost all of the breeds have calculated inbreeding coefficients, and the Ne of a little over 75% of breeds have been estimated. Genetic characterisation studies and the continued monitoring of important genetic parameters such as inbreeding and Ne is essential for the evaluation of genetic variation and health of the population and are important for the determination of adequate breeding strategies. Subsequently, the active participation of students in these types of projects is an important asset to the field of animal genetic resources and can escalate the efforts to fill the existing gaps.

For more information:

- Anna Maria Johansson (anna.johansson@slu.se)

- Karin Olsson (djurvalfard@jordbruksverket.se)